programming coffeescript isomorphic react flux javascript

From Modern C++ to Modern Web Applications 2: Hands On Front-End

In the previous article, I retraced the history of web applications architecture, in comparison with our beloved (and a bit more mature) C++ desktop/mobile applications.

So what we'd like to do now, is create our own isomorphic front-end web application, and see how it is organized, while still keeping our C++ background in the back of our head.

Finding inspiration

The first thing I did was to look at the examples stemming from the AirBnb article I mentioned last time. Their aim is to demonstrate what isomorphic apps are, and how React (facebook's UI components) works. I spent some time fiddling with the coffee-script version of the original AirBnb example.

It's a good starting point to get more familiar with coffee-script, and understand how the server and client part interact, with some common libraries, just like we would do in a C/C++ program that forks.

Here are my conclusions after trying to understand and extend this code.

The take-aways

Grunt

Grunt is a make equivalent that you can setup to:

- Convert coffeescript to javascript

- Convert JSX (React's format) to javascript

- Pack all the client code into a single JS bundle

- Run node server

- ...

I read there are replacements for Grunt now. Honestly, you could be using the plain old make or .sh scripts, that would make little to no difference to me...

Coffee-script

Coffeescript is quite easy to learn and is much more expressive and concise than plain javascript. Look at the comparison on their page, especially when writing classes, you'll be convinced.

In fact it is so easy to read, that you don't even have to use the JSX format to write your React components. This component renders two sub-components (ScheduleTable and SlotCreator) in just a few lines:

{% highlight coffeescript linenos %} React = require 'react' ScheduleTable = require './ScheduleTable' SlotCreator = require './SlotCreator'

{h1, h2, div} = React.DOM

module.exports = React.createClass

render: -> div null, h1 null, "Schedule" React.createElement ScheduleTable h2 null, "Add Slot:" React.createElement SlotCreator {% endhighlight %}

Here is a quick survival guide to read coffeescript:

- Indentation is important

- Most parenthesis and braces are optional

returnkeyword is optional, the last expression in your function gives the return value- Anonymous functions are written

(x, y) -> x * y - Named functions are just the same, but assigned to a variable:

func = (x, y) -> x * y, that you can then call withfunc 3, 4orfunc(3, 4) @is a shortcut forthis., so@render()callsthis.render()- Most list comprehension and sequences generation from python, ruby, elixir, etc. work. Just check the syntax first :)

The ugly part

Appart from the points mentioned above, the AirBnb example is a bit of a mess. Which is not a critic really, since it still was the beginning of isomorphic applications at the time it was written.

The server spawns an Express application, which contains routes to fetch resources (i.e. /api/posts.json).

A completely different router, instanciated from a third-party routing lib, handles the client-facing routes, like /posts. It is used both on the server and in the browser, but because the syntax is different for both, there is a lot of ugly code to adapt it, depending on who uses it, and some more adaptation code on the server to be able to plug this router on the existing Express router there...

So we have 2 routers with different syntaxes, whose only purpose is to fetch resources and feed them to the appropriate view. But what if we need something more complex? Where does the logic go?

What we need is a formal way to organize our app, that we could just publish on our company's wiki, and that you could just give to newcomers when they need to add a feature.

Facebook to the rescue: Flux

The guys at Facebook asked themselves the exact same questions, and came up with an architecture. They called it Flux. Not another framework, just an architecture. Follow it if you want, build on it, do what you want. I like that.

The principles

What happens if we look at an MVC architecture, and try to apply it in an isomorphic context?

When a user requests a page to the server, we would need to instanciate some model objects, with data taken from a service or a database, use them to populate our views, and pass it along to the browser so that it can display them, and that the user can interact with the rest of the app.

Which means that we need:

- a router that can be used identically on both sides,

- a model which could be serialized on the server and deserialized in the browser

- a place to put any code related to user interactions (e.g. when user clicks here, do that)

- a place to put the logic related to our model (e.g. make a properly formatted string from the date and time fields from our database)

- a simple flow that avoids us from thinking for 3 hours about which part is responsible for which task.

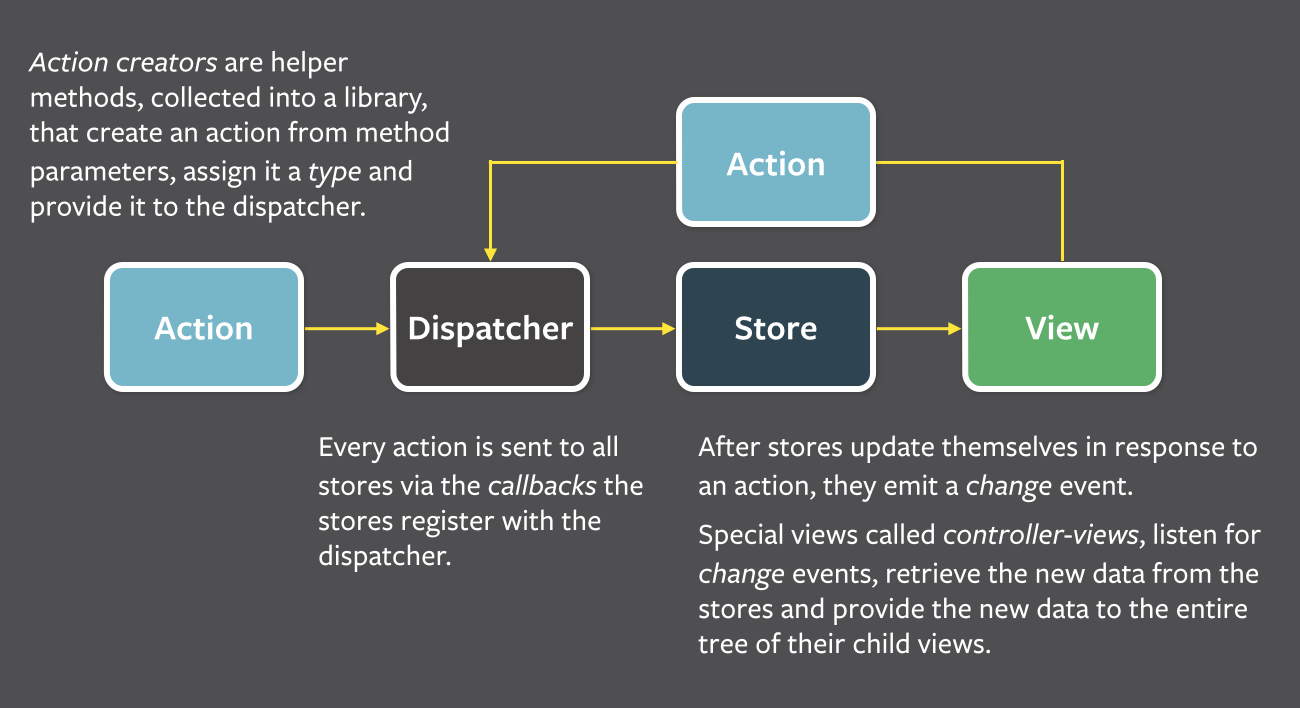

Flux's take on this is the following:

Stores

They are some kind of higher level models. One store doesn't necessarily match with one resource in your backend. For example, in a chat application displaying emojis in each message, you could handle everything in a MessageStore, even though you have one API endpoint to retrieve the messages, and a different endpoint to retrieve the images for emojis.

Also, they are not composable. Meaning that a store will not contain another store. So that's a little bit different from what you would have in the model layer of a traditional MVC app.

Stores can:

- Get data from other stores

- Update views with fresh data

Views

Views are pretty much as dumb as what we have in an MVP model (presented in my [last article]({% post_url 2015-02-03-web-apps-for-cpp-programmers %})).

Views can:

- Dispatch an action (e.g. user clicking the "submit" button will dispatch "checkout-order")

- Receive an update from Stores

- Query stores to retrieve their initial state.

Some views are quite generic, like a fancy date picker which only needs an initial date to display, and an action to trigger when the user changes it.

Others are more complex, and composed of smaller views. Like a registration form showing a date picker, a photo selector, and taking updates from several stores. These fancy views that are responsible for redrawing other views and receiving updates are called "Controller-Views". Fortunately, React is smart enough, and will actually redraw just the views whose properties have changed.

Dispatcher

It is responsible to notify all the concerned stores for a particular action.

Why is there a Dispatcher, and not a direct call from Actions to Stores?

Let's take the flight reservation page example from the Flux docs. Say we have a dropdown list of countries and an dropdown list of cities. Changing the country will obviously update the list of cities because if I select a flight departing from France I want to see the french airports appear in the other dropdown. So when the country changes, two stores are impacted: the country store, and the city store.

One way to do this would be for the "update-country" action to first trigger a countryStore.updateCountry(...) which would set its internal variable for currentCountry, then trigger cityStore.updateCountry(...), to update the list of available cities.

Another way would be to make the CountryStore dispatch another action to update its buddy, cityStore.

But the guys at Facebook considered that both these methods were potentially going against the flow they're trying to create, and were harder to debug. Instead, the recommended way is to:

- Dispatch the "update-country" action to both

CountryStoreandCityStore - Let

CountryStoreupdate itself with the new country first - Let

CityStoreupdate the view with the correct cities list - Enforcing this exact order of execution by explicitly mentioning in the

CityStorehandler that it needs theCountryStoreto handle the event first.

This way, a certain coding hygiene can be enforced, thus:

- Forbidding actions dispatching from the Stores

- Keeping actions really simple, so that unit-testing stores by themselves makes sense, even without the corresponding actions code.

More details on the dispatcher are available on the Fluxxor page.

Actions

They could also be called "Commands", because they're just functions that trigger some handler in one or several stores (most of the time).

As we'll see later, libraries like Yahoo's Fluxible let you do more stuff inside actions. For instance if you need to poll your API for data, you'll want to dispatch a given action in case of success, and a different one in case of failure. But since we can't dispatch actions from within a store, such tasks have to be done from inside the action itself, like this:

{% highlight coffeescript linenos %} module.exports = (context, payload, done) ->

message = authorName: payload.authorName isRead: true text: payload.text

The handler in our MessageStore would display this message in grey

until it has been stored successfully

context.dispatch 'RECEIVE_MESSAGES', [message]

Asynchronously store the new message via our API

context.service.create 'message', message, {}, (err) -> if err ## Problem => Mark the message as failed in the view context.dispatch 'RECEIVE_MESSAGES_FAILURE', [message] else ## Confirmed => Mark the message as successfully sent context.dispatch 'RECEIVE_MESSAGES_SUCCESS', [message] done() {% endhighlight %}

In practice, Actions are slightly more complex and error prone than a dumb "function call" as described in the original Flux docs...

The major drawback here, is that it allows you to break the flow described above for the Dispatcher. If you wanted to, you could call several store handlers from within the same action when one would suffice.

For example, take the following Fluxible action:

{% highlight coffeescript linenos %} module.exports = (context, payload, done) ->

message = authorName: payload.authorName isRead: true text: payload.text

context.dispatch 'RECEIVE_MESSAGES', [message] context.dispatch 'INCREMENT_AUTHOR_MSG_COUNT', payload.authorName {% endhighlight %}

Instead, you should have the MessageStore handle this incrementation, since it is not really a functional Action, rather a book-keeping task that comes with the reception of a message.

Of course, one could argue that the same mistake could be done at view (aka component) level by successively dispatching RECEIVE_MESSAGES and INCREMENT_AUTHOR_MSG_COUNT after a click on the "send message" button.

The point is, creating the right actions or sequence of actions is, in my experience, the trickiest part of the architecture. Don't do the same mistakes I did ;)

Wrapping it all together

Since Facebook didn't release all their libraries yet, Yahoo came up with a bunch of modules to fill the gaps, called Fluxible that you can use to implement this app organization. Now you have a Router, a Dispatcher, Stores and a Fetcher (which "services" the resources from your REST API, database, ...), in addition to the now widely used React components.

A real life example : ObeseBird

After all those buzzwords, it is now my turn to come up with a stupid name.

I decided to create an application to post tweets of specific categories to my twitter feed following a given schedule. This way I could automagically post about music every Wednesday at noon, and about tech every Monday morning.

I know there are tools to do that already. But we didn't make them ourselves, so, by definition, they suck (don't deny it, we all think that way!).

Also, this will allow us to:

- Code a front-end to really understand what we've only touched so far

- Talk about an awesome language, Elixir

- Code the back-end using Elixir + Phoenix

But this article is long enough as it is, so I'm afraid you'll have to wait for the next one. Tons of fun ahead!

[Next article here.]({% post_url 2015-03-03-obese-bird-ui %})